Introduction

The impact of a dam extends further than a flooded landscape. In 1964 the construction of Akosombo Dam was finished in West-African Ghana, and some 8,482 km2 of land was inundated. Up until today, Lake Volta is according to surface area the largest man-made lake in the world. Since it was formed almost 50 years ago, the impact has had sufficient opportunity to crystallize in the surrounding environment.

IMAGE 1.MIGRATION

As a direct result of the inundation, 80,000 people living in over 500 villages were forced to leave their homes. Resettlement villages were created by the Volta River Authority (VRA), but provided insufficient livelihoods. This triggered secondary migration, initially to the cities, and as the lake begun to stabilize, people started to move to the waterside. By 1968, over 60% of the resettled farmers had migrated away from state cooperatives and farms.

IMAGE 2.STATEMENT

A preventive planning measure was taken, but it entailed nothing more than a law referring to a topographical line at 280ft, invisible in the field. So despite planning precautions, the riparian landscape of Lake Volta is these days host to informal activities and over 1,500 small settlements along its 4,800 kilometers of lakeshore. The principal reason for setting up there is the huge potential for activities in the primary sector brought by the large body of water. The inhabitants active in the primary sector attract further informal activities related to processing and trade etc. as well as settlement. Sedimentation caused by this human activity is threatening the future production of hydro-electric power by the Akosombo Dam.

IMAGE 3.MAP

The spatial trajectory of the settlements around the lake shows that historically, villages were already had intimately relation with water: they were situated close to the former Volta River (in white, flooded settlements in light orange). However, the environment has changed significantly, and establishing a relation with the lake required a re-invention of the former pattern.

IMAGE 4.DRAWDOWNZONE

At the end of 2008, several settlements around the lake were visited to perform this case study. Those with a high potential for development (based on characteristics such a accessibility by road and/or water, relief, neighboring communities etc.) are marked by an orange plus. Exemplary for the issues and opportunities is the village of Kpando Torkor in the Volta Region (indicated by the box).

The height of the lake's water level throughout the year is highly unpredictable. The tributaries have a large catchment area, stretching all the way into Burkina Faso. Bottleneck Akosombo Dam makes the water rise from September, peaking in November, after which it slowly drops. The decreasing frequency of rains on the one hand, and the increasing intensity on the other, associated with global climate change in this part of the world, is a serious issue. The flood risk increases, as the water level rises higher and more rapidly. Upstream dams, outside of the Ghanaian territory, that open their sluices when the pressure becomes too high to handle, add additional influx.

During the fieldwork in the fall of 2008, the village encountered a heavy flood. The predictions were that this would become more common rather than a singular 'coincidental' exception became reality when the heavy rainfalls of 2009 (600.000 people in the whole of West-Africa affected, 25 casualties in Ghana) and 2010 (1.6 million affected, 30 casualties in Ghana) again swept away the livelihood of the Lakeside villagers.

However, a positive effect of the annual changes in water level is a strip of fertile grounds that is exposed when the water recedes: the drawdown zone, 100 to 150 meters wide depending on the topography. For a few months, from mid-February until June drawdown agriculture can be practiced there, and it has become a common way of subsistence farming around the lake. But food insecurity expands as this practice is only semi-legal, and it reliability diminishes with climate change.

IMAGE 5.PROBLEMATICS

The landscape is vulnerable and the mounting pressure is causing the system to degrade. The current uniform government policy is proving inadequate to the task.

Design: An integrated landscape based strategy for guiding informal activities and settlement in the riparian landscape

This project assesses the possibility of creating within this complex relationship a spatial, sustainable and integrated solution by means of a strategy that is rooted in the landscape. Our intention is to find a balance between sustaining and further enhancing the quality of life in the informal settlements and protecting the surroundings against sedimentation and degradation.

CONCEPT

The graphic representation shows the drawdown magnitude within the landscape. As the levels are highly unpredictable, a large zone is susceptible to flooding and thus unsafe. The primary goal is to rule out the risk of flooding of houses as much as possible, while on the other hand, the natural cycle of periodic submergence of the land needs to continue to exist. This effectively means establishing a larger distance between the lakeside and its settlers, creating a productive zone in between. The concept is based on the spatial structure of the riparian landscape, strengthening it with infrastructure to create a framework. The road is linked to the 300 ft contour line to stimulate settlements to develop higher up the slope, away from the Lake. It functions a physical structuring element, creating visual clarity in the spatial organization. All the other design principles and interventions are linked to the main road, striving to trigger self-steering development. The optimal location to attract people and trigger small-scale urban development is at an intersection with an existing road. So at strategic locations infrastructural facilities are linked to the network, guiding the informal activities and settlements, developing into centralities.

The concept functions as a magnet with a positive and a negative pole. The flood risk could be the negative pole; by increasing the distance to the lake flood can be reduced, at the same it creates a safer situation in times of extreme water levels. Accesses to basic services and opportunities for development are the positive poles; which attracts concentrated development of private initiatives and settlement. In addition, the pressure is relieved of the most vulnerable parts of the landscape near the Lakeside.

IMAGE 6.SOLUTIONS

This flexible method of planning allows people to settle spontaneously and develop the settlement in their own way, while at the same time they are prepared for development and a growing population. This incentive planning approach uses limited financial resources and minimal land ownership. The design provides solutions to a number of basic problems such as poor accessibility and erratic and unreliable power supply, integrating them with such basic facilities as clean drinking water, sanitation, safe living conditions and attractive outdoor space.

Creating a productive zone and improving water retention in the landscape, which makes an increase in agricultural production possible, enhance food security. Improved agricultural techniques protect the environmental system from erosion, depletion and pollution.

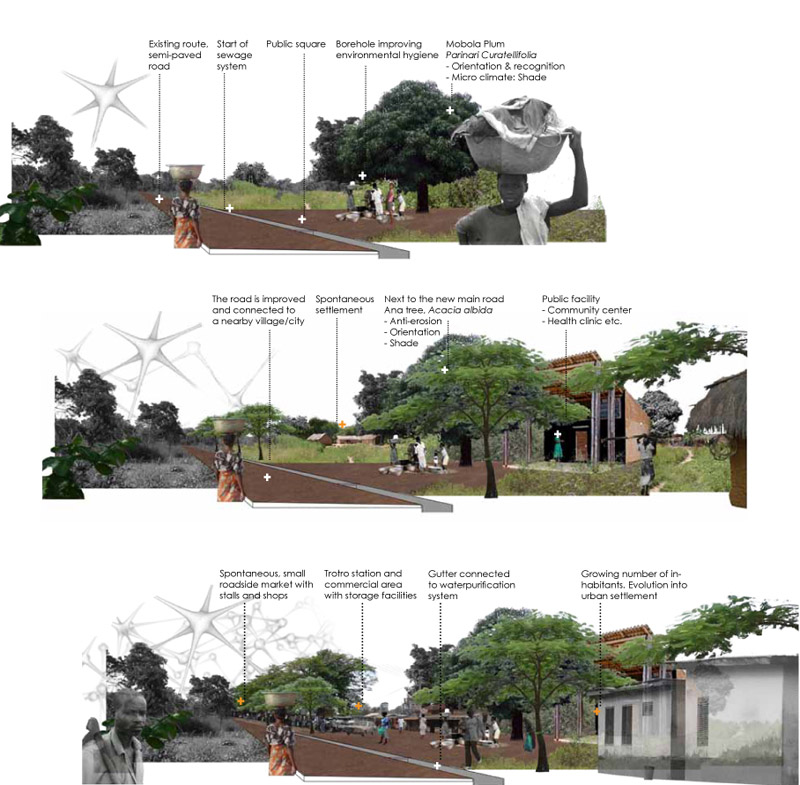

IMAGE 7.PHASES

Phased development:

(1) The start of incentive planning is made with the implementation of basic infrastructure and facilities - This can be (parts of) an existing route, or a new semi-paved road, combined with the preparation for a sewage system. Vital is a public square with a borehole to improve environmental hygiene. For orientation and recognition a Mobola Plum (Parinari Curatellifolia) is planted, creating a shady and comfortable microclimate.

(2) Evoked development - People are attracted to the safer, higher location. The road is improved and connected to a nearby village/city. Spontaneous settlement occurs along the paths. Next to the new main road Ana trees (Acacia Alba) are planted, to prevent erosion that could damage the road and to provide orientation in the landscape and shade along the route. The square is elaborated by a public facility, for example a combination of a community and health care center, or a school.

(3) Urban development along the road, with a commercial area – Spontaneously stalls and shops can pop up, together forming a small, roadside market. A Trotro station (for small taxi buses) and commercial area with storage facilities complete the activities. The gutter, created in the initial steps, should become connected to the water purification system. With a growing number of inhabitants, the pioneers starts to evolve into an urban settlement.

Conclusion

This case study can be regarded as activism (landscape) architecture. We would like the Ghanaian government (and governments dealing with similar cases) to see that the developments around the lake are inevitable but can also be looked as a positive asset. The riparian landscape offers the potential to support livelihood, without jeopardizing Akosombo dam's efficiency and durability.

But there are also universal lessons for regional landscape planning and settlement development that can be learned from this case study. By abandoning the government's 'contour line – approach' and replacing it by a physical and thus visual element as a road, we proposed two key strategies:

(1) coupling landscape and infrastructure, enforcing each other. This results in a site-specific approach to development, which takes local characteristics into account.

(2) time as a key factor, both as uncertainty (threat) and spontaneity (opportunity). Not a blueprint master plan but a framework plan based on parameters forms the base. At selected areas settlement and growth can be stimulated by incentives, leaving space for change as the inhabited landscape transforms.